I’ve teased writing this article since I started writing this blog. I spent a few years at an old job developing workforce data reports; the client would ask a (usually poorly-worded) question and we’d figure out what they meant, pour through databases to grab relevant fields, write queries, summarize findings, and deliver. We would usually add one more section right below the report title: caveats. These could range from excluding certain categories in the dataset to assumptions we made while processing to describing shortcomings in the data itself. Caveats served in part to make sure the end users didn’t draw any conclusions based on misunderstandings, and as a bit of CYA for ourselves.

I written extensively about Harry Potter. Fantasy is my choice genre and I grew up of an age with Harry as the books released. I don’t want to repeat myself too thoroughly here (for full details, a la Gilderoy Lockhart, see my published works). But I’ve read/listened to the series a dozen times, twice been to The Wizarding World of Harry Potter in Orlando, dressed up for the movie premiers, visited the studio tour in London, and used a Dumbledore quote during my wedding. I adore this series. The writing, pacing, foresight, and themes are spectacular (please, please write me if you disagree. I will discuss). Yet every time I’ve mentioned the series, I’ve been reminded of those old workforce reports and felt the need to caveat.

Rowling created wonderful characters exploring the impacts and deriding the outcomes of prejudice. We saw and were repulsed by the treatment Hermione received as she was called a ‘Mudblood’ (someone born to non-magical parents) and the policies enacted during the seventh and final book with the villain’s regime in power in government. We felt the prejudice Hagrid faced as half-giant. The strength in these characters lay not just in rising above others’ assumptions but in embracing them. Hermione would not have been half the witch she was without her Muggle (non-magic) parentage. Not because she had to ‘prove’ herself, but because I can think of nothing more exciting than to be thrust into an incredible new world at the age of 11. In her shoes I would want to learn everything I could, too.

Hagrid is loyal and forgives rapidly. He wears his heart on his sleeve. But his giant roots strengthen his character. We know his violence isn’t reckless- his gentleness defines him. But it’s there when he needs it, and at 10-12 feet and hands described as ‘dustbin lid-sized,’ he’s a threat. “I am what I am, an’ I’m not ashamed, ‘Never be ashamed,’ my ol’ dad used ter say, ‘there’s some who’ll hold it against you, but they’re not worth botherin’ with.” Rowling gave us these characters, and a story whose central themes were the triumph of love over fear and hate and the importance of picking what is right over what is easy. “It is our choices,” reads one of the more iconic quotes from the series, “that show what we truly are. Far more than our abilities.”

I say all this to draw contrast with Rowling’s comments on transgender women over the last two years. I’ll link her response to let you read and interpret but they boil down to 1) desire to transition is just a phase that women will regret and 2) transgender women aren’t ‘real’ women and their existence detracts from feminism as a whole. She also falls back on stereotypes. More on this from me a bit later this post. For now- I want to just raise the dilemma. How should one reconcile the positivity of experience with Harry Potter the story with the negativity of the author?

Authors don’t own their stories

No surprises, but I will not offer a prescriptive answer to that question (especially in terms of how to treat Harry Potter moving forward). Boycotts are effective tools when trying to get a person or company to change specific practices. Not allowing your workers to unionize? I’ll use this other company until you do. Donating to anti-gay groups? I’ll go elsewhere for a chicken sandwich until you stop. But boycotting is a harder line when you’re not trying to change a specific practice but instead wanting to punish. And doubly hard when there isn’t an alternative product. There’s no clear one:one ‘I will switch from Goya beans to Bush’s’ when it comes to pop culture. By all means I’m far from saying don’t spend any more money on Harry Potter if you feel that would be an endorsement of Rowling’s anti-trans views.

Instead I want to tackle how to feel about the experiences you’ve had to-date with Harry Potter. Can authors’ views undercut the message you derived from their stories? A clear answer from me for once: no. Authors do not own their stories. A storyteller evokes the outline of the world but the reader gets to walk away with the image. Once you hit publish, that’s it. The readers, observers, listeners, or players are now free to draw their own conclusions, fill in any gaps, and choose their takeaways. I’ll use an easy, positive example of Rowling’s. After the end of the books, Rowling responded to a fan question by saying the character Dumbledore was gay. I love the interpretation. I agree with it. It makes magnificent sense given the story complexities about his relationship with Grindelwald. But she had no right to say that as a declarative statement. Unless something is explicitly said in the story (and even then!) authors don’t own our interpretations. I urge you not to think of Rowling at all, for good or ill, as you reflect on the themes from HP.

On gender as a whole

As I mentioned I’ve dawdled on writing this article. Not because of any of the content above. Nor because I’m wary of discussing ‘politics.’ This isn’t a political discussion. Politics are how much should we invest in one program over another, what should our trade policies be, etc. These instead are human rights discussions. I have nothing but contempt for those who claim they themselves are being discriminated against because they’re refused leeway to discriminate. If your ‘earnestly held’ values say some people or groups are less deserving of humanity or rights, find different values. And stop using conjured hypotheticals to defend your hate. Rowling makes the claim (echoed recently by politicians trying to rile up Christian conservatives) that the existence of trans women provides some sort of insidious Trojan Horse for male predators to attack women in bathrooms and changing rooms. ‘Our hate of trans people is ACTUALLY geared toward protecting women. That’s why we’re going to make a lot of scary statements about locker rooms and care about women’s sports for the first and only time in our lives.’ Leering at, harassing, or assaulting someone is still not allowed. But I’m digressing.

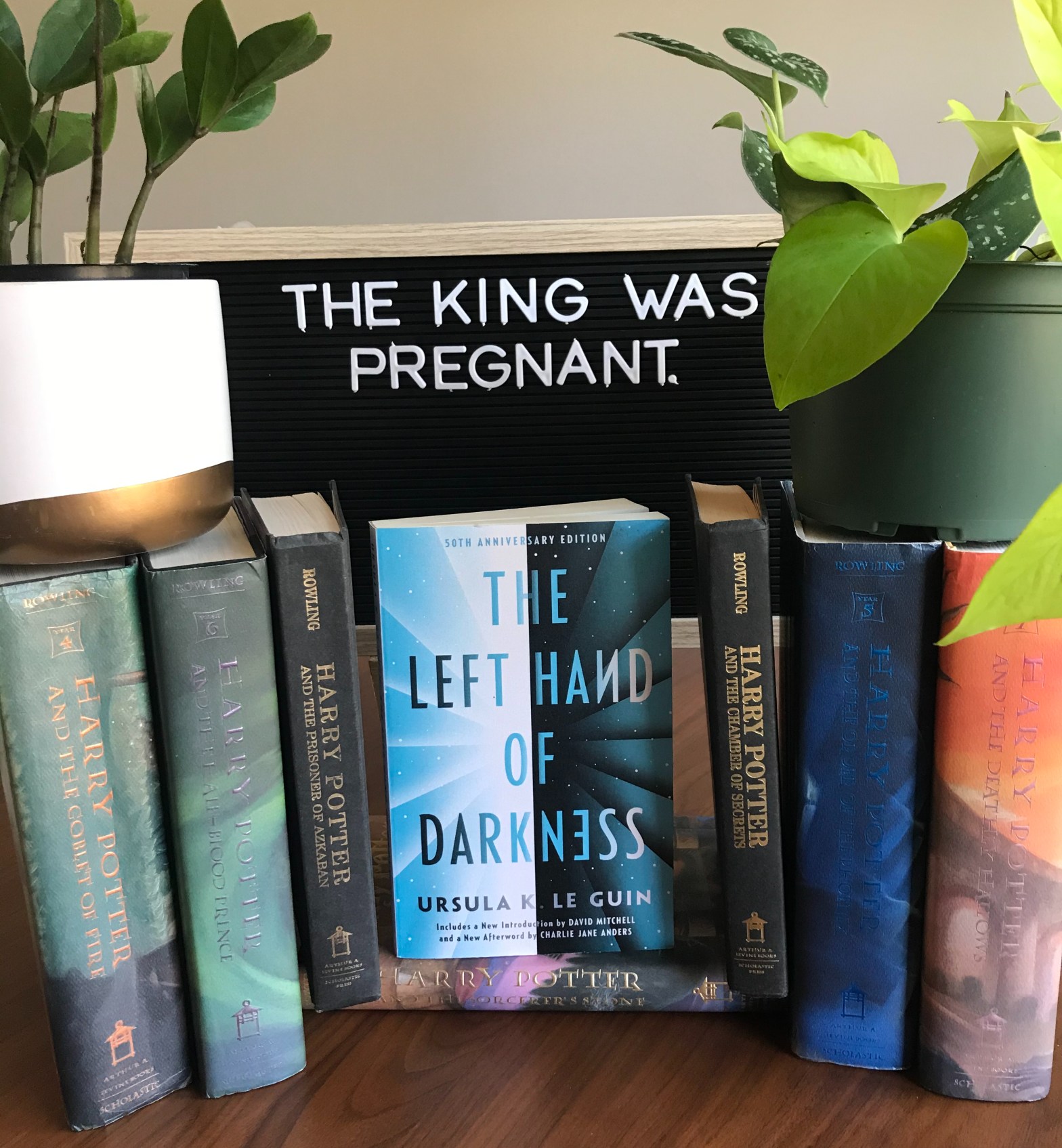

No, I’ve been wary of writing this article because I thought it disingenous to do so without giving my own views on gender and 1) I wanted a literary framework and 2) I’m terrified of getting it wrong. I don’t yet have an answer for number 2. But my read of The Left Hand of Darkness this past week opened the door for me to have this (one-sided) conversation. The story centers around the character Genly Ai, an envoy from a coalition of planets known as the Ekumen. In this universe a series of planets were settled by human forerunners; each planet lost knowledge of these forerunners and envoys make new ‘first contacts’ to encourage joining of the coalition. The races of these worlds are fundamentally human but with sometimes profound differences. Ai is an alien visiting the world of Gethen, known to the Ekumen as Winter.

Winter’s inhabitants, as I said, are human. Ai is a little taller than average, and a little darker of skin. But the profound difference lies in Winter’s gender, sex, and sexuality. For 26 days a month Winter’s people are androgynous until they enter a type of estrous cycle called Kemmer. Once in Kemmer however, and with a partner also in Kemmer, Gethenians present secondary sex characteristics. The catch: you don’t know until Kemmer which partner will present as ‘male’ and which as ‘female’ and it changes from Kemmer-to-Kemmer. The same person can be capable to birth children in one Kemmer, and sire them in another. Thus Winter has no gender. The narrator (our stand-in) struggles to reconcile this with his own rigid binary gender structure. I knew none of this when I started the book. I recognized the name of the author (Ursula K. LeGuin) and wanted to give it a try.

Ai’s struggles mirror what I view as the keenest issue: the concept of gender as a whole. My assumption (and the part I’m afraid I have wrong) is a lot of the anguish faced by trans people lies in the fact that their mental self-image does not match what society believes someone with their secondary sex characteristics should present. Therefore, if that person feels a stronger kinship with the gender that does not match their body’s presentation, they should take steps to conform to that role instead. Given this assumption, my issue lies with gender roles in and of themselves. If we had no concept of what it means to be a ‘man’ or a ‘woman’ would anyone ever feel out of place, or that mismatch with their own body?

My view is we would be in a better place if could mimic the Gentheians. Winter’s inhabitants don’t lack for individuality or personality. They have pursuits and passions, interests, religions, and love. They have strong self-image and even stronger senses (perhaps problematically) of honor. But none of that self image concerns gender. A quote from the afterword by Charlie Jane Anders: ‘Maybe our rigid gender binary is just as made-up as their neutral-except-once-a-month gender is. Maybe our government-issued pronouns and official stereotypes don’t have to define us always. Especially for my fellow trans and nonbinary people, a story that undermines the assumptions behind coercive labels feels magical.’

Leave a comment or shoot me an email to let me know what you think!

So I’ll preface this by saying that I think you and I are more or less equal in HP knowledge and fandom. I think you’d admit to that? That doesn’t really matter though–suffice to say that we walked around the track quizzing each other on our Harry Potter spell knowledge in 2007 and were still going to specialty Harry Potter trivias together ten years later. The books “incontrovertibly” got me through my teens and ’20’s, I loved HP Binge Mode, and last night, in classic fashion, I Sorted all the people in the room.

I’ve definitely reckoned with the problem of the author whose views become distasteful before. Evelyn Waugh wrote Brideshead Revisited, the book that helped me come to terms with being gay, but later became a stodgy conservative who bemoaned the popularity of his best known work, which was written in his “youthful, hedonistic” days. I don’t think I would have liked him personally forever, and the same can be said of the many authors who changed into people that would never have created their early art. That said, when you encounter this situation with an author who is dead, it is much easier to distance yourself from them as a person–it’s easier to appreciate them as they were at that time in their life and not bother with what they were or what they became. You can say “well, they were a product of their times, and I’m therefore going to appreciate the value here and disregard the things that don’t jive with me for one reason or another, that whole section that ‘didn’t age well.'”

I can’t do that with Harry Potter. It wasn’t really until this year (quite late to the…party?) that I became aware of the full scope of “J.K. Rowling, TERF extraordinaire.” The tweets are utterly damning. The double-down on the tweets is damning. It’s not even like she has an opinion that she’s keeping to herself–she has actively gone out of her way to be cruel. She’s published an ENTIRE NOVEL in which the serial killer is a man pretending to be a woman.

Even worse than reading her TERFy takes is reading the response of trans people that, like us, grew up in those magical 7-9 years, in lockstep with Harry’s age. They were struggling with their identity and psychologically relying, like I was, on Harry Potter to get them through that extra (extra) dimension of teenage insecurity that comes with being LGBTQ+. It is devastating, living to see our Liberal hero of the aughts become the villain.

The thing is, JKR is alive and well, she’s a billionaire, and she shows no signs of recanting on her stance. It’s really at odds with not only Harry Potter, but with some of the compassion she shows in The Casual Vacancy, that pointed rebuke of middle class prejudice and hypocrisy (a la The Dursleys). “Boycotting her brand” is pointless unless it makes you, as an individual, feel better. There is no amount of money she could lose that would be impactful in any way, shape, or form. So what then? What do you do with a story you love authored by someone that ACTIVELY practices the very prejudice and discrimination she rails against in the books? She’s become a figurehead for TERFs around the world, and that influence actually DOES sway minds and hearts, and real trans people suffer for it. Maybe it’s not measurable, maybe she’s not sitting in Parliament enacting laws, but when you’ve sold billions of copies of your books in a multitude of languages, people pay attention to what you say. Legislators justify themselves with the words from your pen and your mouth.

Getting back to the premise of how you deal with this, that “author’s don’t own their stories”–I disagree. Much of the litigation she’s been in has been asserting the claim that she does, in fact, own every scrap of IP surrounding her stories (which, it should be said, is how we got the delightful “Puffs”). I loved the post-HPDH “Dumbledore was gay the whole time” reveal, and I loved it even more when this Lupin background came out https://www.wizardingworld.com/writing-by-jk-rowling/remus-lupin, in which she talks about how she based Lycanthropy and its perception off of elements of the AIDS epidemic. It’s a meaningful addition for me, and it tailors perfectly with how his character is presented in the books. However, this idea of the post-mortem addition unfortunately cuts the other way.

How can you tell a living author that the story is not theirs and that instead it is yours, in your mind and heart, and that it means something to you other than what they intended it to mean, that the meaning is very much at odds with who they now are? I believe in the form of literary criticism focused on what the book means to the reader–what we get from stories absolutely changes as we change, and I don’t mean to denigrate the value of that. I just find it kind of absurd to think that my interpretation of authorial intent is superior to what the living author says about their life and how their (the author’s) story influenced their creation.

To return to my original scenario, I obviously don’t agree with every view held by every author of every book I’ve ever read, and I think it would be supremely foolish to devalue those books on my shelf authored by someone that did not comport with the perfect ideal of a modern progressive liberal (nobody comports with this ideal, and I certainly don’t). However, it’s a little easier temporally cage an author that’s dead, rather than one who, in addition to occasionally continuing to expand [cough cough, *retcon*] the Potterverse, actively uses her significant wealth and influence to discriminate against trans people (particularly women) and perpetuate prejudice. It’s this ongoing damage and the way this contravenes the themes of the books that make the story hers, unfortunately. I hope that one day I’ll read the books again and love them again, but I have yet to achieve the required cognitive dissonance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for a super well thought out reply Joe! I’ve read through it a few times and I don’t think I disagree with anything you said. I wonder if my relationship with the story is different only because I never really leaned into Pottermore. Basically- the story has been ‘dead’ to me since 2007 and thus very much in the realm of postmortem critique.

I can absolutely see your point in the value of having a source loved by millions take a certain stand, and the possibility for damage as well. Basically it’s the sliding scale of value between Rowling saying ‘the prejudice/vileness faced by Lupin for his lycanthropy is a metaphor for how society treats those with AIDS’ vs a reader independently viewing it as the metaphor and Rowling saying ‘oh I didn’t see it that way but it makes sense’ vs a reader having that view and Rowling saying ‘no, you’re wrong. Also people with AIDS should be outcasts.’ Your point is that while there’s still value in the second, the first is ideal, and the third is the territory we’re at now with her TERFiness?

LikeLike