Back in February I wrote in a post on the power of seeing yourself in stories about my enjoyment of seeing archetypical Jewish characters on The West Wing. At the time I wanted to differentiate between stories where a character’s racial identity is an essential part of their background, but not the focus of the story itself. That said I’m not remotely opposed to the latter category. I’ve twice had the chance to see live productions of Fiddler on the Roof (arguably the most well-known play/movie about the Jewish experience and assuming of course I’m not underestimating the following of An American Tail, the animated feature starring Fievel Mousekewitz).

Fiddler centers on Tevye, a milkman in the fictional village of Anatevka in the Pale of Settlement in Imperial Russia near the beginning of the 1900s. Ostensibly framed by the marriages of Tevye’s three eldest daughters, Fiddler’s meta-story is the villager’s attempts to maintain their Jewish customs and traditions in a changing world and under the rumored threats of pogroms and expulsion. The play opens with Tevye monologuing on the value of tradition (tradition!) as it defines daily life. There are traditions for everything in Anatevka/Jewish life writ large. How to sleep, how to eat, how to work, how to wear clothes. ‘You may ask,’ ruminates Tevye, ‘how did this tradition get started? I’ll tell you.’ a pause. ‘I don’t know. But it’s a tradition’!

I love the play. No small part of that is it tells my own family’s backstory; it was a favorite of my great-grandmother (born in Russia in 1897, emigrating to the US in her teens, and living past my own Bar Mitzvah in 2003). But a larger part is watching other (in this case fictional) people living the traditions in which you yourself were raised. I grew up in an area with very few other Jewish people. My extended family was just a short trip across the bridge (which made for large, loud, and lovely Jewish holidays), but my day-to-day existence was by-and-large gentile-saturated.

Look. I’m not a strong advocate for tradition for tradition’s sake. I think I covered ‘no true Scotsman’ in a previous post but another commonly used logical fallacy is called ‘appeal to tradition’ (or argumentum ad antiquitatem if you’re on a Latin kick). It’s exactly what it sounds like- ‘this is right because we’ve always done it this way.’ Those leveraging this fallacy aren’t arguing the merits of their case, but it has a strong appeal to those who are more conservatively inclined. And please note that I mean conservative in the most literal sense (not just politically)- those who need a reason to do something a different way, rather than a reason why not.

A lighthearted example of these clashing mindsets has played out recently in major league baseball. The average game ballooned in length from about two hours and thirty minutes in 1980 to over three hours today. To speed up the game, baseball introduced changes including giving the option to let a batter go to first base without the pitcher throwing any pitches (in the old system, the pitcher would have to intentionally throw four balls outside of the strike zone), mandating pitchers face a minimum number of batters to avoid the long breaks around pitching changes, and perhaps most controversially, starting extra innings (when you keep playing after the game is tied after the normal nine innings) with a runner on base to increase the scoring. Traditionalists argue baseball has been around for 150 years, why change it. Revolutionary voices say baseball has always been changing and work is needed to keep the game fresh/popular.

Less lighthearted (though, given the vitriol I’ve seen online about the above maybe it wasn’t the best lighthearted example) is when appeal to tradition is used as a cudgel. ‘Marriage has historically been between a man and a woman, why should we allow anything else’ or ‘what do you mean you want to be a nurse, that’s for women.’ In Fiddler Tevye (spoilers here, though this play came out 57 years ago) becomes estranged to one of his daughters due to his inability to accept her marriage outside the faith. Anatevka, like most such villages where Jews lived for thousands of years, collapsed after the Imperial government ordered eviction. Most of its inhabitants, like my great-grandmother, left for America.

I’ll conclude this section of the post by saying I don’t mean to decry tradition. Knowing you speak, dress, or celebrate the same way as those before you lends a little borrowed gravity to your own actions. You can go to any major league baseball stadium in America (and one in Canada) and you’ll stand up in the middle of the 7th inning and sing ‘Take me Out to the Ballgame.’ Traditions build that sense of community that we so crave as social animals. But they can also cause harm when they outlive their usefulness or refuse to bend and thus break and disappear entirely.

The Holiday Tradition

Stories have an outsized place in our personal or family traditions, especially as it comes to (religious) holidays. I’d wager most of you have a favorite Christmas movie or six you watch annually come December (Elf, The Grinch Who Stole Christmas, National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation, and The Nightmare Before Christmas for me, the last of which does double-duty for Halloween). My best friend’s dad, with his New Orleans roots, does a family recitation of the Cajun Night Before Christmas. My wife and I just wrapped our annual listen/watch of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar for Easter. A stories’ themes, and the occasion of their telling, evoke that nostalgic sense of belonging, even for people like me who are not religious.

Judaism is rife with this storytelling tradition. The week-to-week practice at Synagogue is starting at the beginning of the Jewish holy book called the Torah at New Years (Rosh Hashanah/Yom Kippur), reading a subsequent section every week during services, and literally rolling it back to start again next year. Hannukah tells the story of Judah and the Maccabees, Purim of Esther and Haman. And Passover (the whole point of me writing this article, a point that only took me ten or so paragraphs to reach) of Moses and the biblical story of Exodus. I’ll resist for now the urge to draw up a character study (Moses is one of the most common examples of a storytelling theme called the hero’s journey) because this is not that kind of post. It’s an article about tradition. And this year I acutely felt the absence of one of my favorite annual traditions: the Passover Seder.

The Story of the Passover

Before I get back to the Seder- a quick refresher. The story of Exodus relates the story of Moses and the deliverance of the Jewish people from slavery in Ancient Egypt. I do want to caveat this story is allegorical; as far as I’ve read there’s no archaeological evidence of a mass Jewish enslavement in Egypt or anything in support of the popular cultural image of Jews building the pyramids or anything of the like. I don’t say this to take away from the tale- Plato wasn’t actually shoving people into a cave under his oikos but we still draw lessons. And there are plenty of other tragedies for which a period of bondage may serve as a metaphor. I’m just a stickler for historicity.

But to Moses. According to the story Pharaoh (the ruler of Egypt) feared the rise of the Israelites and thus enslaved them and ordered the casting of their newborn male children into the river Nile. One Israelite woman, in an effort to save her son, instead floated him down the river in a basket where he was later discovered by Pharaoh’s daughter, who brings the child (Moses) up as her own. Aware of his origins, Moses murders an Egyptian slave overseer and flees to the desert. He marries, starts a life as a shepherd, and presumably settles down but for the appearance of God in the form of the Burning Bush. God commands Moses return to Egypt and free his people. Moses does so- visiting increasingly severe plagues on the Egyptians culminating in the tenth and final plague where God passes through the land of Egypt to slay all the Egyptian first born. The plague passes over the Israelites (earlier commanded to mark their doorposts with lamb’s blood), hence the name of the holiday- Passover. Moses leads the people of Egypt, parts the Red Sea (which collapses back on Pharaoh’s forces) and lives happily ever after in that he wanders 40 years through the desert and dies in exile.

The Seder

And so, back to the present day. Jews celebrate Passover through a custom called the Seder in which we all gather at a table to tell the story, perform specified ceremonies, sing songs, eat prescribed foods (while steadfastly avoid others), and generally have a lovely wine-fueled time. We like to kvetch about the length of the Seder (and therefore the delay before we reach the page marking ‘The Festive Meal’) but complaining is an important part of the tradition. I’ve been to Seders in a few different formats but most often at my grandmother’s house with a large contingent of cousins (I’m the third oldest of 17 of us on my mother’s side, with a new generation on the way). It’s loud and crowded and people throw toys and spill soup and I’ve missed it dearly during the pandemic. Last year I managed a small celebration with just my immediate family, but this year with my parents in the middle of a move, my brother spending the holiday with his girlfriend’s family, and hectic work schedules for all parties involved, I didn’t really celebrate. I missed it. And so- I invite you to run through our Seder traditions with me below.

The Table

Our night begins with all of trying to find our nametag at one of several tables arrayed through the house. Inevitably at least one family (usually mine) is late and people argue back-and-forth over whether we should wait for them but the belated party arrives in the nick of time, everyone makes a joke about it being Elijah (more on that in a moment) and we get started. The table is set with plates, soup bowls, and wine glasses for everyone with a few non-commonplace items like the Seder plate, bowls of saltwater and parsley, small pamphlet-like books called Haggadahs, and an extra ornamental wine glass set aside for the prophet Elijah (for whom the door is left open every year, hence the aforementioned jokes about the late arrivals). The chairs themselves are also (capacity-depending) augmented with small pillows or cushions.

The Opening Prayers

The Seder leader (theoretically) gets everyone’s attention and we open with a blessing for the wine, the first of four glasses we are commanded to drink that night, and one which we’re supposed to enjoy in a reclined position. Everyone competes to lounge as much as is possible in a folding chair. We move to bless the washing of the hands, the dipping of parsley into saltwater (bear with me) and the breaking of a piece of matzah (that flat, cracker-like bread most associated with the holiday). The leader holds the matzah aloft and reads ‘this is the bread of affliction which our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt; let all those who are hungry, enter and eat thereof; and all who are in distress, come and celebrate the Passover.’

The Four Questions

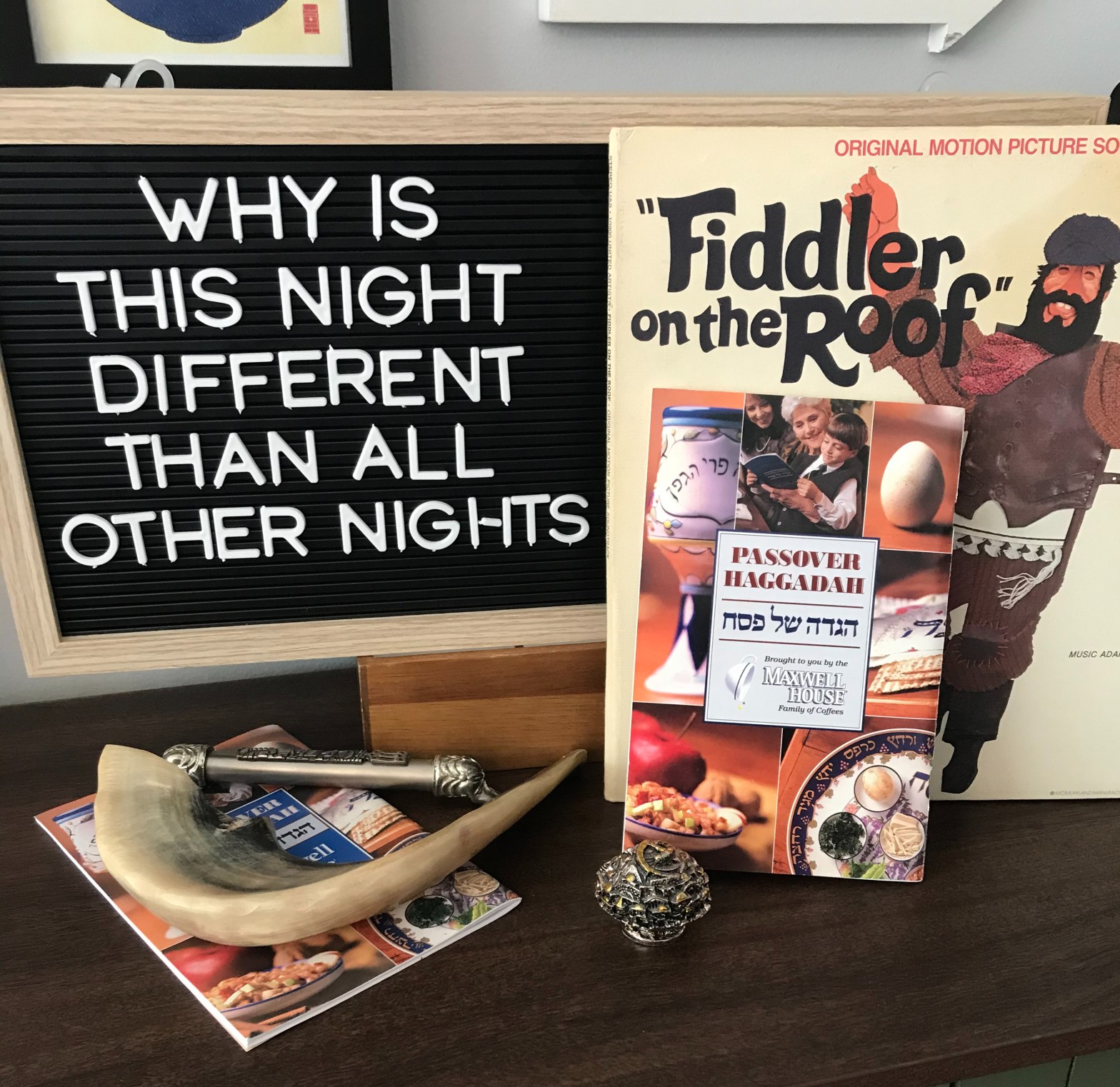

At this point we recite the Four Questions- a little bit of table setting pointing out some peculiarities of the Seder which we will answer in due course over the evening. Traditionally the youngest attendee asks the questions (first in Hebrew, and again in English) but as we haven’t had young children in the family for a while, and because this is one of the few segments in which we remember both the Hebrew and the tune, we’ll all sing together. The questions open with the words transcribed as ‘manishtanaw halailaw hazeh meekawl halaylos’ and translated as ‘why is this night different than all other nights’? Like one of those ‘find the differences between the two pictures’ puzzles we call out the unleavened bread, the bitter herbs, the dipping of the food, and the pillows/reclining position.

The Communal Read, Song Breaks, the Plagues

At this point we go around the table reading paragraphs aloud as we tell the Passover story. After a few sections on semantics (note: Jews love semantics. It’s one of my favorite parts of the faith. Very rarely is something presented as absolute) we come to an allegory of a father (and I’d argue not a great parent) and his four sons, one each who is wise, wicked, simple, and lacking the capacity to inquire. We take an aside to pull up separately printed sheets and sing this sub-story to the tune of ‘Old Clementine.’ This marks the first of several musical breaks from the ritual including a rousing rendition of ‘Take me Out to the Seder’ and a song about frogs.

From here we dive into quick section of passages arguing about the literality of metaphors and trying to make each other giggle through creative emphasis of words such as ‘breasts’ and ‘bondage.’ The story covers the promises God made to the Israelites in a sort of respectful guilt trip- the gist of which is ‘hey, you promised you’d look out for us. You’re powerful and mighty and we respect you but also a bit of a hand here would be nice.’ From there a quick litany of the atrocities of the enslavement before segueing into a recap of the plagues and deliverance. Careful not to fall for tricks here- sometimes you’re instructed to lift your wine glass but not to drink. If you mess up you’ll get booed.

The Seder now covers the aforementioned 10 plagues inflicted upon the Egyptian people. I struggle with the messaging in this part of the story. After each plague Pharaoh is inclined to let the Jewish people go, but the passages reference God ‘hardening Pharaoh’s heart’ in a bit of a ‘no, no, I’m not done with you’ moment. But back to the story. We recite the plagues in both Hebrew and English, spilling a drop of our wine onto our plates with each name to symbolize a lost sweetness and that we’re not to rejoice in destruction. Dawm, tz’fardaya, keeneem, awrov, dever, sc’cheen, bawrawd, arbeh, chosech, makas b’choros. Blood, frogs (hence the song, and cue my cousins releasing wind-up frog toys on the table), vermin, wild beasts, pestilence, boils, hail (ping pong balls in the air), locusts, darkness, and the slaying of the first born.

More Readings, Dayenu, the Answers

From here a few passages debating numbers of plagues, a bit of a drawn out math problem, and a reference to ‘the Finger of God’ (cue my father demonstrating a rude hand gesture). At this point we reach the second built-in Hebrew song from the Seder that most of us think we know. The Dayenu- ‘it would have been enough’ – runs through a lengthy list of favors from God and extols that each one individually would have been sufficient. We always think we know the words, but really we just know the chorus which we sing with vigor while mumbling the rest.

Finally some answers to the four questions! The unleavened bread: our ancestors didn’t have time to let the bread rise as they fled Egypt. The bitter herb (horseradish): the bitter existence in bondage. The dipping (mixed messaging here): freedom, but the choice of dip (saltwater) the tears/sweat of the slaves. The reclining: more luxury/freedom.

Ceremonial H’orderves and the Festive Meal

A couple more prayers, including once more the hands and the matzah. A quick programming note- the matzah we broke before, one of the pieces is now missing! But more on that shortly. We take a pinch of mawror (horseradish) and combine it with charoset, an apple/nut mixture, bless it, eat it, and make various faces depending how strong the horseradish was that year. From here, same combo but this time take a little bit of matzah and make a sandwich. Next the Festive Meal! Much rejoicing, and we dive into matzah ball soup, chopped liver, gefilte fish (a poached mixture of ground, deboned white fish), and maybe some salmon. Definitely a few acquired tastes in there. Main course probably brisket, lamb, and chicken with some veggies on the side. We eat way, way too much, continue drinking wine, and generally try to save just a little room for dessert which we’d dive right into except, wait!

The Hostage Negotiation

In a startling, Shamalan-esque twist, the Seder leader hid half the broken piece of matzah from earlier in the evening somewhere in the house. The children set off to find this piece (known as the Afikomen) and upon its finding, ransom it back to the Seder leader. Until the Afikomen is returned (and tested to make sure it fits the broken half), no dessert can be set on the table and we are prevented from leaving by what I can only assume is the full force of Jewish law. Cue one more song (‘Don’t Sit on the Afikomen,’ relating the tragic incident of one’s aunt unwittingly crushing the Afikomen and trapping the family at dinner) and dessert is served. A hallmark of Passover is the abstention from leavened bread, or bread products in general, so dessert is heavy on macaroons and pavlova. We eat even more, tuck a few macaroons in the pocket for a late-night nosh, and make our sleepy ways back home.

Have a favorite storytelling tradition, or one with meaning to you or your loved ones? Let me know. And Chag Pesach Sameach!

One thought on “I don’t know- but it’s a tradition”