I half-lied. We’re absolutely going to talk about the power to enact political or institutional change in stories. But the second half of the line has naught to do with anything. I just firmly adhere to the philosophy that one should, paraphrasing Rahm Emmanuel (perhaps the premier American power-broker of the 2000s), ‘never allow a good [Voldemort quote] go to waste.’ This is far from a new philosophical stance for me. I wrote most of the ceremony script for our wedding; my wife and I are firmly non religious but our families have varying levels of commitment to the Jewish and Baptist faiths. As such I took special care to avoid minefields. The final ceremony (officiated by a dear family friend and rife with literary allusions) saw Voldemort defeat any sort of deity by a final score of two mentions to zero. But enough of what is rapidly becoming my traditional non-sequitur opening paragraph and on to the subject at hand.

Power. Work devoured my soul a little this week and the free time I managed resolved into enjoyment of our first days above 60 degrees in what I can only assume has been 3-5 years. All that is to say I gave no thought to this week’s article and was on the verge of deferring to next week until I saw some of the reactions to Meghan Markle and Prince Harry’s interview. For context (and I’m far from a royal-watcher, so forgive any mistakes) Meghan and Harry announced their decision to formally step back as senior members of the British Royal Family in January of 2020. These roles, including titles and inheritance, also came with significant obligations and strict personal limitations under formal protocols.

Now fourteen months later Meghan and Harry sat down with Oprah to give their account of ‘Megxit’ as it was dubbed. Most jarring (but I wish more surprising) among the litany of reasons were the royal institution’s preoccupation with self-image rather than support of Meghan as she dealt with mental health struggles and an actual, presumably breathing, member of the Royal Family expressing ‘concern’ over just how dark the skin of their child, Archie, would be. Reactions to the interview varied. Some expressed support for the couple and others viewed any sort of public criticism of the royal institution as anathema.

Meghan, as always, drew the brunt of the criticism. Much of it, as always, with racial undertones (or overtones). Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge and Melania Trump are ‘classy, ‘refined,’ ‘elegant.’ Meghan Markle and Michelle Obama are instead ‘uppity,’ ‘ungrateful,’ or in one particularly egregious case ‘an ape in heels.’ But I’ve yet to find a group more defensive or self-aggrieved than people making racist comments when you point out they are, in fact, making racist comments. So instead I’ll focus on one more aspect I saw of the criticism: people like Meghan Markle (with ‘power’ and prestige) have no right to complain. That the image of a wealthy couple in an idyllic setting telling their story to a billionaire is somehow hypocritical.

My favorite counter to this criticism was a quote attributed to Russell Brand (though I always assume quotes are apocryphal unless captured on video): ‘when I was poor and complained about inequality they said I was bitter; now that I’m rich and I complain about inequality they say I’m a hypocrite. I’m beginning to think they just don’t want to talk about inequality.’ Given these barriers, and the ability of entrenched institutions (like the monarchy) to resist change, how then does one gather power to convincingly make those changes in stories? Chewing on this idea I came up with three categories: the martyr, the infiltrator, and the beacon. Note that I’ll focus on power as it comes specifically to believability in overthrowing/changing entrenched institutions (instead of concepts like magical might or battle prowess). I’d also argue that successful stories often combine all three concepts. But enough caveats. Let’s dive in.

The Martyr

Martyrdom is a broad enough term that we’ll need to spend a moment winnowing our definition. Originally just translating to witness, the word martyr is most widely applied to those willing to endure suffering or else die for their cause. By this application most typical “warrior’s deaths” in stories can be described as martyrdom. Gandalf the Grey in Lord of the Rings, Dobby in The Deathly Hallows, Rue in The Hunger Games. These deaths fit our definition above but do not meet the criteria I’m using to effect institutional change. Deaths are powerful storytelling tools. Character deaths raise the stakes of a story, else motivate a different character to pursue a course of action.

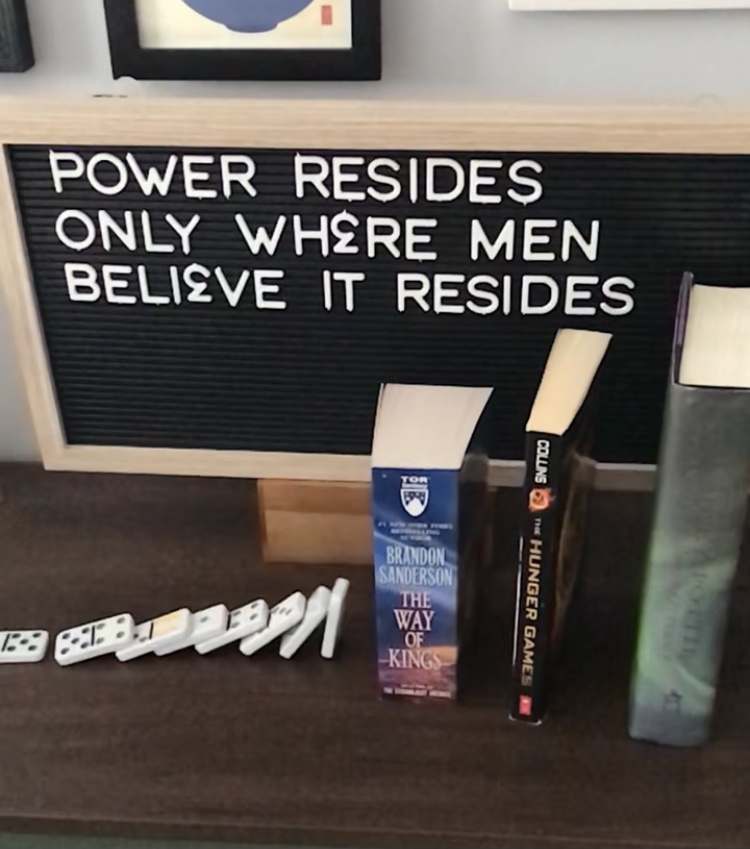

Yet in this case I want to exclude the warrior death definition and instead describe situations where a character takes an action fully intending to die (not just embracing the possibility of death) for the sole purpose of drawing attention to the evils of the system. Io, Persephone of Red Rising, sings a forbidden song knowing her execution will inspire horror of the Reds’ enslavement. Katniss (and Peeta) choose to poison themselves to point out the arbitrary cruelty of the rules for the Hunger Games. Martyrdom in stories can be that spark that lights the fire. But in and of itself it’s an admission that in life that person did not have the power to accomplish their goal. So how then to deal with the dynamic that one cannot effect change without power in the first place?

The Infiltrator

This second category, infiltration, neatly addresses the knot that those with the power to make change are those least likely to want it. Our storytelling trick is thus to take that person with the outside perspective and thrust them into the very institution they want to unseat. Our character gains access through one of two means; actual disguise (Darrow’s carving, Aladdin’s wishes) or access to powers usually reserved for the upper class (Vin in Mistborn, Mare in The Red Queen). Our heroes find allies in these institutions, often an academic-minded love interest (and child of the leader of main political force) who helps our hero navigate this unfamiliar world. Through this infiltration our hero slowly builds up a cadre of allies and can start making small differences in the institution’s actions. However while operating under the guise of ‘the enemy’ the hero cannot fully remake the institution as they will not have the trust of the people he or she is trying to liberate. Luckily there comes that unmasking moment in the story where the hero’s true origins are revealed. At the time this is viewed as a setback; how can our hero retain their power?

The Beacon

The answer is by operating with such perfect precision that no reasonable person can accept the validity of the previous power structure. Are Golds really superior to Reds if a disguised Red excelled at the Institute? Can our society restrict the actions of our women if Hua Mulan served the military with such distinction? Using a character as a beacon is an effective, if not depressing, way to undercut prejudices central to the mythos around powerful institutions. Any small failure of the hero will be used to condemn the entirety of ‘lesser’ race/class/etc. and as justification for the continued existence of the system. In stories, our heroes overcome. Hermione is the best in her year, those who hold her Muggle-born status against her be damned. Kaladin, a darkeyes, can defeat a Shardbearer in single combat.

We love seeing these successes in stories, but it shouldn’t have to come to that. Those from privileged or powerful groups are granted grace for their shortcomings. Those seeking to effect positive changes have manufactured shortcomings used to undercut their message, and then have their anger at the system’s abuse of power held against them.

Let me know what you think!