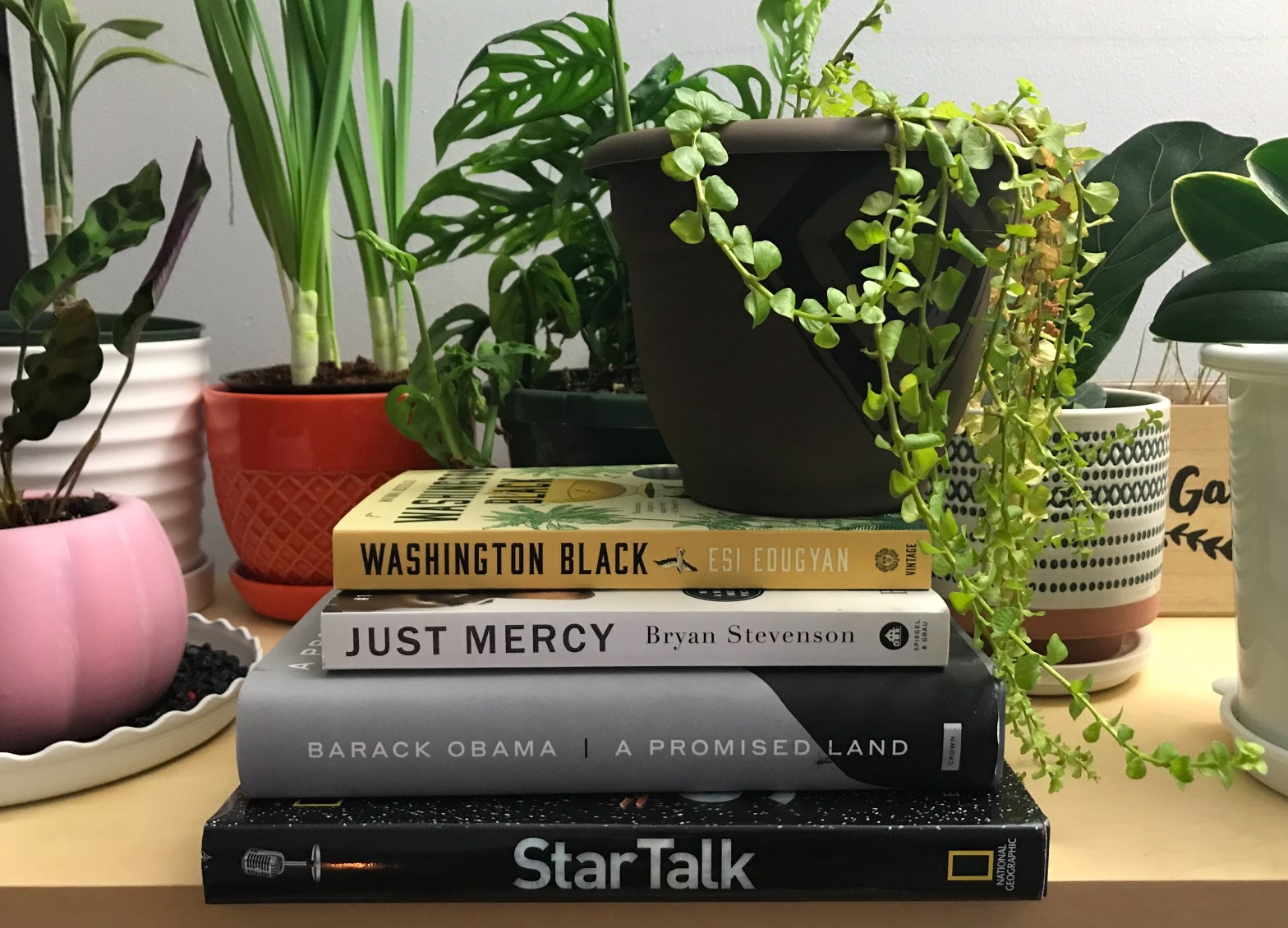

February is Black History Month here in the U.S. and I planned to write about why representation, either as the character or as the storyteller, matters. I do however need to pause for a second. While setting up the photo for this post I was surprised and a little disturbed by how few books I own from black authors. I borrow a fair number of library books and, at least in the last few years, consume the majority of my stories via audiobook. So I could pull a few more from my Audible account. But still. It’s not good. And most of those I do own are non-fiction which is great and lovely and means I’m spending time on the experience. But as I’ve shared in my previous posts, most of what I read is fantasy. So why then, with a few exceptions like NK Jemesin, do I have so few books by black authors, especially in genres I frequent?

I generally fancy myself as somebody who **makes an effort** (cue balloons/confetti/uplifting sound effects). I’m very much on the liberal side of the political aisle but do my due diligence reading right wing news sources and books (and only get ticked a few days a week feeling like these people don’t make the same effort for me). I’m non-religious and culturally Jewish but do the same on other mythologies and traditions and celebrations. But the problems there are twofold. One- that’s really not that much. I’ve seen quotes, memes, etc. circling social media expounding on the idea that knowing a little bit about a subject is worse than knowing nothing at all. Ideally, one who knows nothing would not presume to act on that knowledge. So the theory goes a little bit of wokeness can be more damaging than outright ignorance as those in the former category can do harm while thinking they’re doing good. I get that, but I also reject it. By all means let’s not pretend to know a lot about a subject just because we stayed up until 3AM on Wikipedia a few times. But- this isn’t a binary experience. You don’t have to choose between fully immersing yourself in something and ignoring it all together. I am continually realizing though that as convenient as it is to claim understanding, I’m usually barely dusting the surface.

The second reason is bubbles. Much ado was made about polarization and isolation during the 2016 election and onward. Most Americans are overwhelmingly surrounded by those with similar political reviews, religions, and cultural beliefs. And the availability of social media means that organizations catering to specific views are able to further isolate and prime these bubbles. With all this said- expanding beyond a bubble is doable, it just takes active effort. I was lucky enough to grow up out the outskirts of a major city with all the general mixing of humanity that entails. BUT, as per my first point, that doesn’t eliminate my bubble, just disguises it with a thin veneer of palatability. Almost everyone I grew up with, and still my closest friends, grew up in upper middle class households, went to east coast colleges, studied technical fields, medicine, or law, and are now settling down in their careers or buying houses or whatever it is. There’s a lot of overlap in our tastes. When I watch shows or movies, Netflix offers me similar suggestions. Audible recommends books or authors similar to those I already read. When I follow book accounts on Instagram they’re usually people posting content I already enjoy. If I’m in a bookstore, I’m more likely to buy a book if there’s an endorsement from an author I already like on the cover. My bubble is immensely real.

I’m going to conclude this section by saying I don’t know how to get you to care about diversity of perspective. Studies and decades of findings show the benefit to everything from small communities to companies to countries but if I’m being honest, my main drive here is emotional. Learning something new is a simple and spectacular joy in life, compounded when you have someone who’s passionate about sharing their novel experiences with you. Watching straight, white, predominantly Christian men (a group with which I share three attributes) claim things are meritocracies when they’re disproportionately represented and that something is either a vast progressive conspiracy else a direct attack on them when efforts are made to correct imbalances is hideously frustrating from the outside and I can’t imagine how horrifying from the inside. Where does that leave traditionally underrepresented groups? You push so hard to succeed in a system designed to benefit those who wrote the rules of that bubble only to be told your accomplishments are somehow lesser because you must have had ‘help’? (Also, we all get help all the time. No one has ever done something on their own. But we’re several paragraphs in and we have other things to cover so I’ll wait on that rant).

The storytelling community is not immune from this. The Hugo Awards are generally considered the premier science fiction and fantasy awards, given annually since 1953. In 2015, a group of writers argued the success of stories featuring non-white characters or authors was due not to merit but to undue political correctness on behalf of the awards. A substantial voting bloc of authors banded together to shut out the stories they viewed as too progressive, using the rules of the system to dominate final ballots. Their nominations managed to entirely compose the finalists for five separate categories, forcing the rest of the writers to select ‘No Award’ or else pick a cherrypicked candidate from this voting bloc. These men (and it was mostly men) were so aghast at the idea that people with different backgrounds than theirs were finding success in their system that they used the full weight of that system to shut them out.

I know this isn’t a smooth segue, the above just makes me angry. And a little embarrassed at myself. Looking through my bookshelf means I’m certainly contributing to this broken system. But- on to three types of representation in stories, what I’ll call stereotypical tokenism, generic portrayal, and archetypal identity. I wouldn’t hate better ideas for what to call these, so let me know if you have some after reading. If nothing else these sounds fancy so let’s role with them.

Stereotypical Tokenism

Tokenism in and of itself is defined as making a perfunctory effort to include someone from an underrepresented group to give the appearance of diversity or equality. I’m going to go a step further and add that ‘stereotypical’ modifier to the front to say you include a character from a particular group only to have them act in way that others outside that group expect them to act. I’m trying hard to avoid assessing the value of each of these types of representation in stories but it’s difficult to avoid seeing the harm here. Be it the mammy stereotype employed in old Tom & Jerry cartoons, the workers at the Chinese restaurant from A Christmas Story, or any number of ‘gay best friend’ roles. In these situations, the characters’ whole function is to operate in the periphery of our leads and play out a stereotype. The restaurant workers are inserted so the main characters can ‘hear their strange accents and eat their weird food.’ The gay best friend role doesn’t have their own life, rather they’re supposed to be sassily supportive and defensive of our heroes and validate their choices.

There are a few arguably less harmful examples of this stereotypical tokenism. The easiest are characters who intentionally act the stereotype to try and subvert it. Mel Brooks, one of my all time favorite filmmakers, plays on stereotypes relatively frequently with the expectation the audience or character is supposed to be aware of the stereotype and by playing to it, point out its idiocy. The black railway workers in Blazing Saddles, when told to sing by the overseer expecting a spiritual, instead come back with ‘I Get No Kick from Champagne’ by Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra. Another, I won’t say positive but maybe less harmful, example: a character who plays to a stereotype to get a laugh from that group (as opposed to an outside group). Mel Brooks again, but the traveling mohel from Men in Tights offering circumcisions to the Merry Men. A joke by a Jewish director featuring a Jewish character making Jewish jokes to tickle the Jewish portion of the audience. Even these situations give me pause- do you wind up perpetuating a stereotype even if you’re using it without actually seeking to put down the group? Regardless, for the cases in this paragraph or in the one above, we have situations where a character solely exists to service as a stereotype of a group.

Generic Portrayal

I’ll define generic portrayal as a the situation where someone from a particular group is represented but their group has nothing to do with anything. Consider your typical college advertising flyer, drug commercial, or teen drama show. In these cases we have a character portrayed by a person of color or someone from a marginalized group but that character’s experiences within the community have nothing to do with the character’s motivations or actions. While a neither difficult nor particularly deep change, I hugely support this type of representation whenever possible because a) why not and b) representation allows people to see themselves (or others) thriving in situations they may not have thought possible due to a preconceived notion.

I’ll give the example of casting Dennis Haysbert as President Palmer in the tv show 24. The character’s race and background was not remotely the central point of the story, nor do I remember if the show mentioned the remarkability of having a black president. But this was a full seven years before the election of Barack Obama. I still wonder if the show got some people used to the idea that a person of color could in fact serve as President (shocking I know). This representation ESPECIALLY has merit given the history of white actors and actresses playing people of color in film or television. I’ve also seen a trend of casting a person from a marginalized group in remakes or adaptations. If there’s nothing in a character’s backstory or motivations that require they be from a certain group, then absolutely do this. For instance Noma Dumezweni as Hermione Granger in the West End premier of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child.

Archetypal Identity

My final category here (and what’s left, if you’ve been paying attention) is the representation of a person from a marginalized or minority group where that group is fundamental to the character’s views and actions. I’m guessing it hits a little differently when its your own group, but I always think back to the characters of Josh Lyman and Toby Ziegler in The West Wing. The two characters, senior White House aides, still represent to me the archetypes of the typical American Jewish experience. The show wasn’t about their Jewishness, but I don’t believe the characters would have functioned the same way without their Jewish backgrounds. Same goes here for The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon. It’s a beautifully written book about two cousins working together as they create superhero stories. The novel explores Joe’s anti-Nazi politics and Sammy’s sexuality in one of many periods in American history where both are not to be openly tolerated, but it cannot function without their shared Jewish experience. It’s not a story about being Jewish, but the story would not work without it.

I had this same reaction walking out of Black Panther after it premiered a few years ago. It was obviously not the first blockbuster film exploring black identity, but it was one of the first films I remember seeing where the characters’ blackness was both essential to the story and also not the direct point of the story. This wasn’t a film directly analyzing race relations (though of course the history of colonization and the existence of primarily black ghettos in the U.S. feed into motivations). It wasn’t a film with an interchangeable character who happened to be black, or even a play like Hamilton telling a story with a cast composed almost entirely of people of color, but instead a uniquely black story that didn’t just use race as a framing mechanism to reach a different end.

Closing Thoughts

Writing about race and representation is difficult. I can’t capture someone else’s life and feelings, and I’m coming at this from a straight, white, male perspective. I wrote about events from the last handful of years in this post (2015 for the Hugo Awards, 2018 for Black Panther). But this has been going on forever, examples both good and bad. If I think any of this is new it’s more likely that it’s easy to ignore things that aren’t directly affecting me. It’s never anyone else’s job to educate you when you’re wrong. I need to take a serious look at my reading lists. But I still will ask you to let me know if you have author recommendations or forums or communities to follow.

There’s a lot to unpack here, but have any thoughts? Leave a comment or shoot me an email in my contact section.

One thought on “Seeing Yourself in Stories”